As the 20th anniversary of September 11, 2001 nears, there will be many valuable reflections about that horrific day and about the subsequent “global war on terror” that devastated countless lives around the world. My own focus here is narrower: to briefly consider this disturbing two-decade period in relation to the American Psychological Association (APA) and professional psychology in the United States.

In the days following the terrorist attacks that targeted New York City and Washington, D.C., it quickly became apparent that the White House, the Department of Defense, and the CIA were prepared to ignore well-established international laws and human rights standards in pursuit of our adversaries. But at that time, it was less immediately obvious that some members of my own profession—fellow psychologists—would choose to embrace and participate in the merciless “dark side” operations that took place at secret overseas “black sites,” at the Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan, at the Guantanamo Bay detention facility in Cuba, and beyond. And then, as events unfolded further, it became even more surprising that—through acts of commission and omission—these abusive and sometimes torturous operations would also find support within the leadership of the APA.

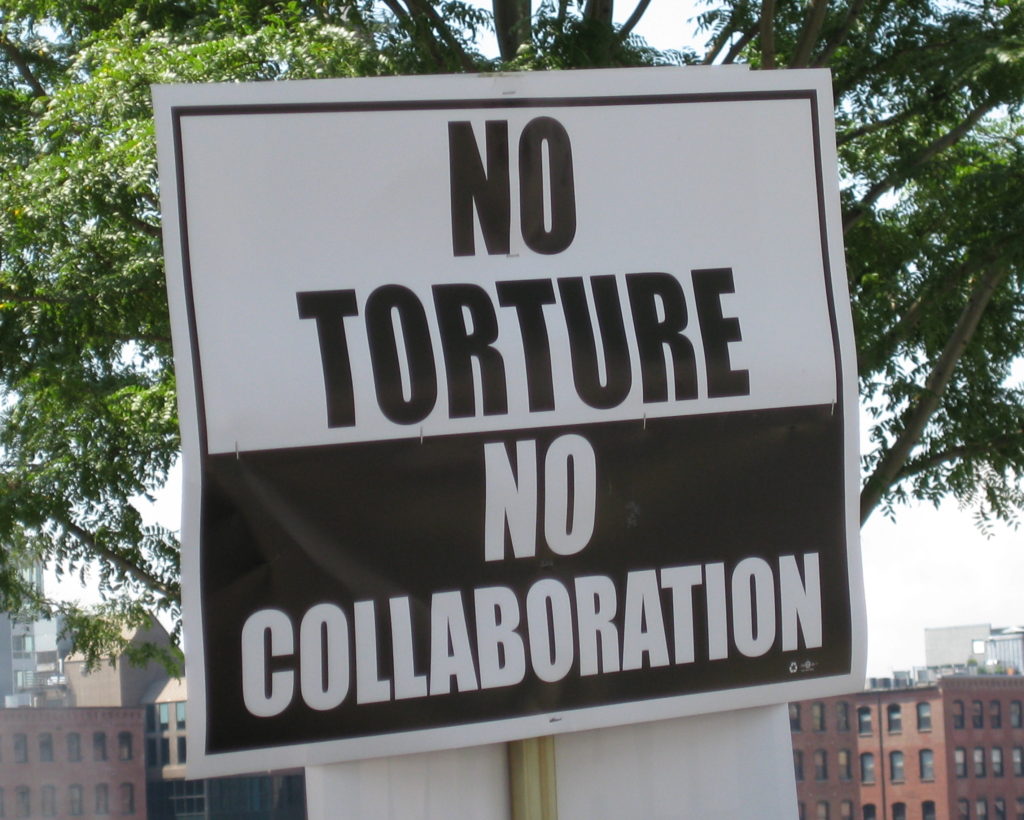

At any point, the APA could have joined with concerned human rights groups in seeking to constrain a U.S. military-intelligence establishment set on unbridled retribution that brutalized prisoners and diminished the country’s moral standing around the world. But for the world’s largest organization of psychologists, that tragically proved to be the proverbial road not taken.

To its credit, the APA did quickly mobilize its disaster response network of expert practitioners who worked with the Red Cross in offering psychological support to rescue workers and families of the victims of 9/11. But the APA moved just as rapidly in a very different direction, working to ensure that the Bush Administration—having promised a “crusade” with the “full wrath” of the United States—would view the association as a valued war-on-terror partner.

In addition to meetings on Capitol Hill, the APA organized invitation-only conferences and workshops that focused on psychology’s potential contributions to ethically fraught counter-terrorism initiatives, with attendees from the CIA and other government agencies. These and similar outreach efforts continued unabated even as credible media reports emerged indicating that prisoners were being abused and that psychologists were involved in their mistreatment. Throughout these years, it seemed that the APA’s focus was almost always on promoting what its members were capable of doing, and hardly ever on emphasizing what they should never do.

The APA’s most consequential step down this ill-considered path was its 2005 task force on Psychological Ethics and National Security (PENS). After a single weekend of meetings, the group concluded that it was indeed ethical for psychologists to participate in war-on-terror detention and interrogation operations—despite the profession’s do-no-harm ethical foundations and growing evidence of institutionalized prisoner abuse by U.S. forces. The PENS process was also rife with significant problems, including the predominance of military-intelligence representatives among the task force members; conflicts of interest among some of the participants; irregularities in the procedures adopted for both the meeting and the report; and an “emergency” approval vote that bypassed the APA’s full governing body.

Nevertheless, APA leaders anticipated that the PENS Report would extinguish the fires of controversy within the profession. Instead, the report spurred the emergence and organization of vocal dissident psychologists—through groups like the Coalition for an Ethical Psychology, Psychologists for an Ethical APA, and Psychologists for Social Responsibility—who opposed the APA’s deferential and accommodative war-on-terror policies. Over the next decade, the association leadership’s primary response to this opposition was to block all serious reform efforts. Their tactics included the adoption of weak, loophole-filled anti-torture resolutions that fell short of actually prohibiting abuse; the failure to enforce a membership-wide referendum that required the removal of psychologists from Guantanamo; the refusal by the ethics committee to modify a key standard that permitted a “just following orders” defense by psychologists involved in abuse; the undermining of an initiative to annul and repudiate the PENS Report; and the repeated failure to adequately investigate and pursue sanctions against psychologists alleged to have been involved in torture and abuse.

Despite these obstacles, dissident psychologists persisted. The tide finally turned in 2014, when revelations of APA wrongdoing appeared in a book by Pulitzer-Prize-winning investigative journalist James Risen. The book confirmed many of the claims that dissidents had previously made, but the greater public attention Risen brought led the APA’s board of directors to grudgingly authorize an independent investigation of the association. That months-long investigation—informally known as the Hoffman Report after the attorney who led the review—found that APA leaders, over a period of years, had indeed secretly collaborated with representatives of the military-intelligence establishment to ensure that psychologists would be able to continue their involvement in internationally condemned detention and interrogation operations. When these findings were released in 2015, they led to long-overdue changes within the APA, including the near-unanimous adoption of a new policy prohibiting military psychologists from serving at Guantanamo or other sites that violated international law.

But reactionary and retaliatory responses quickly followed from individuals and groups seeking to turn back the clock on these reforms. Many of those involved in these regressive efforts had been identified in the Hoffman Report as active facilitators or knowing bystanders during the APA’s many years of support for morally bereft operations by the Pentagon and the CIA. Their retrograde campaign—continuing to this day—has been multifaceted: misleading attempts to discredit the Hoffman Report; official resolutions designed to suppress that report’s findings; the threat and the filing of formal ethics charges against dissident psychologists; defamation lawsuits against the law firm that conducted the independent review and the APA itself; and efforts aimed at returning military psychologists to Guantanamo.

As the upcoming anniversary of 9/11 approaches, the APA’s ethics reforms that constrain the involvement of psychologists in national security detention and interrogation operations still remain in place. But they are fragile and under assault. Particularly worrisome in this regard is the growth of a specialized domain within “operational psychology”—one where individuals are targeted for harm rather than healing; where voluntary informed consent is absent; and where activities are conducted in classified settings beyond the ready reach of outside ethical oversight. This “gloves off” weaponization of psychology diverges dramatically from the core commitments that guide the daily work of almost all other psychologists—including the vast majority of military psychologists—who work as healthcare providers, researchers, teachers, and consultants.

That’s why it’s especially important that this small contingent not succeed in creating false divisions within the profession as they strive to garner broader support for their own work and careers. The real divide isn’t between psychologists who are employed by the military or intelligence agencies and those who work in the civil sector. Nor is the real divide between psychologists who are healthcare practitioners and those who work in non-clinical areas. The divide that truly matters is the one that separates psychologists who prioritize ethics and human rights from those who would abandon these guideposts in favor of expediency and opportunity.

The past twenty years should be remembered as a critical and painful chapter in the history of U.S. psychology: the misguided enmeshment of psychologists and psychological science in the worst of the so-called war on terror; the unconscionable abuses perpetrated by members of the profession; and the APA’s own failure to tenaciously defend “do no harm” principles during times of uncertainty and threat. At the same time, the lessons to be learned extend beyond the field of psychology alone. They apply in significant measure to any profession whenever powerful institutional actors and government agencies turn to them for their expert contributions to ethically suspect endeavors.

In this context, the APA stands as an illuminating and tragic case study. Yet today, key leaders of the association appear all too eager to leave consideration of past mistakes and transgressions behind. But to do that would be irresponsible, so long as influential figures and forces continue to defend the involvement of psychologists in ruthless military-intelligence operations and seek to ensure that these roles will be available in the future. Adding further to the possible peril ahead is the reality that both major political parties have been unwilling to hold past perpetrators of war-on-terror abuses and torture accountable. This only makes it more likely that depraved methods of detention and interrogation will someday be contemplated again—and perhaps sooner than we imagine. Reflecting on the damage done to so many lives and to the profession’s cherished principles over the past twenty years, the APA can’t afford to get it wrong the next time around.