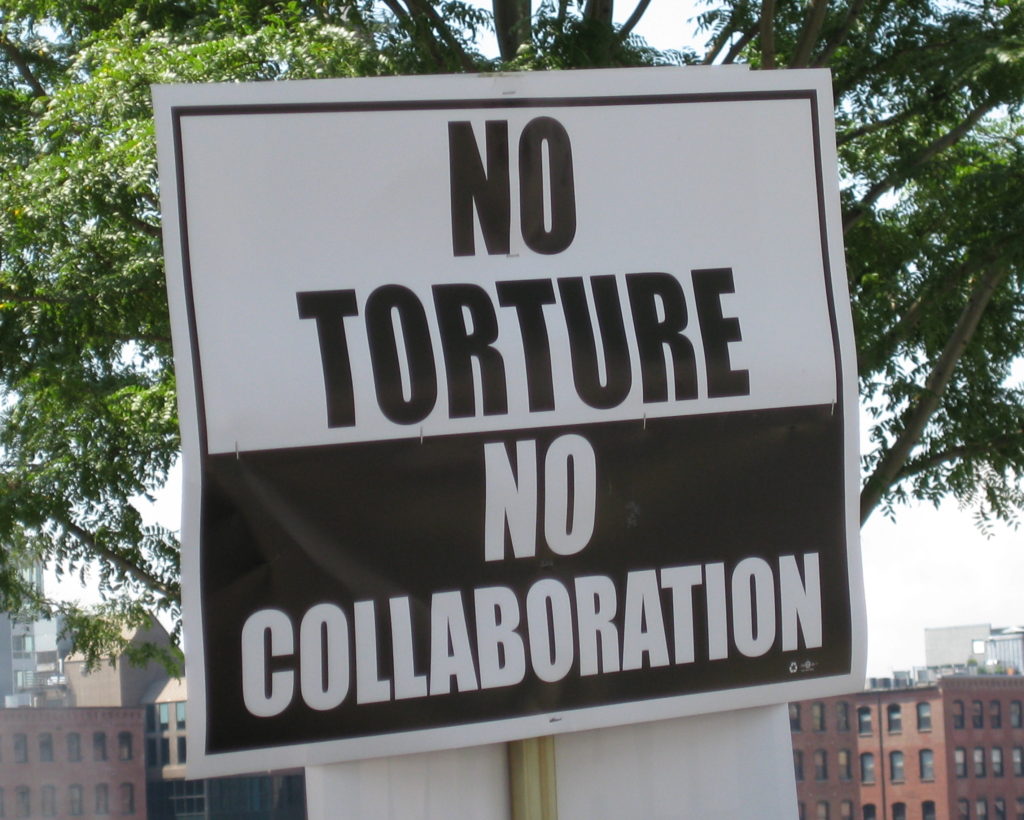

Next month will mark the 20th anniversary of the opening of the U.S. detention center at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. In the years since January 11, 2002, nearly 800 “detainees”—few with any meaningful connections to international terrorism—have been imprisoned there, where they have been subjected to abuse and, in some cases, torture. From the outset, members of my own profession—psychologists—played key roles in operations at Guantanamo, CIA “black sites,” and other overseas detention facilities. Their involvement included designing and implementing inhumane conditions of confinement and brutal techniques of interrogation.

Among the most pervasive of the methods used were solitary confinement, where prolonged isolation could extend for weeks or months, sometimes in empty cells and total darkness; sleep deprivation, in which prisoners were kept awake for days at a time by bright lights, loud music, intermittent slaps, or other noxious means; sexual and cultural humiliation, including forced nudity and sexually provocative and insulting behavior by interrogators; and the use of threats to generate fears of injury and death, ranging from snarling military dogs to confinement in coffin-like boxes to mock executions.

This, then, was the context six years ago when an extensive independent investigation uncovered compelling evidence that leaders of the American Psychological Association (APA)—the world’s largest organization of psychologists—had failed to adequately defend the profession’s fundamental do-no-harm ethical principles. Instead, they had opted to support and preserve the continuing involvement of psychologists in these operations, despite mounting reports of their complicity in “war on terror” excesses. In response to the investigation’s disturbing findings, the APA instituted a series of valuable ethics reforms and apologized to its membership and to psychologists worldwide for having abandoned the profession’s core values.

But the APA’s leadership has failed to issue the most important apology of all: to the hundreds of prisoners at Guantanamo and elsewhere who have suffered grievous harm as the association pursued a misguided agenda. Whereas other human rights organizations decried the Bush Administration’s violations of international law and basic decency, the APA maintained that the participation of psychologists kept these much-maligned detention and interrogation operations “safe, legal, ethical, and effective.” Rather than using its influence in the nation’s corridors of power to demand better protection for these prisoners, the APA chose to cast doubt on credible reports implicating psychologists in abusive and torturous treatment.

An official apology from the APA to the predominantly Muslim prisoners—and their families and communities—who have been victimized by the cruel, inhuman, and degrading misuse of psychological practice is now long overdue. The continuing absence of such an apology raises the worrisome prospect that the APA, after all these years, still remains unwilling to fully acknowledge and accept responsibility for the dire consequences linked to its apparent prioritization of political expediency and other considerations over professional ethics and human rights.

Psychologists and the APA should certainly understand the lasting impact of the extreme abuse suffered by many war-on-terror prisoners. Indeed, the deep psychic wounds of those tortured can persist without end. Survivors of psychological torture often experience overwhelming feelings of helplessness, shame, and disconnection from other people, the result of harrowing mistreatment at the hands of another human being. They can be haunted by posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression; by flashbacks and nightmares; and by feelings that safety and solace are impossible to achieve.

These harms are vivid reminders that the victims of abuse and torture at Guantanamo deserve more than an apology. They are entitled to support for their long-term rehabilitation, and the APA should work to make this a reality. With both trauma-related expertise and considerable financial resources, the association is well-positioned to facilitate assistance to former prisoners and their families who are interested in obtaining mental health care. Substantial recurring contributions to organizations that provide relevant services should become a regular part of the APA’s own annual giving. Undoubtedly, the association should also join other human rights groups in publicly calling for the permanent closure of Guantanamo.

Beyond the benefits to Guantanamo’s survivors, an apology and related ameliorative actions can serve to demonstrate an ongoing commitment by the APA to remembering and repairing its past transgressions—and to avoiding them in the future.