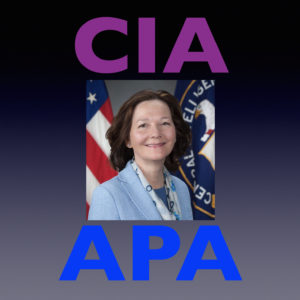

The journey to redemption is long and often tempest-tossed. But the American Psychological Association (APA) took another noteworthy step last week when CEO Arthur Evans Jr. sent a letter to the Senate Intelligence Committee, expressing concern over President Trump’s nomination of Gina Haspel as director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Amid heated debate over whether Haspel is qualified or appropriate for the position, the public record is clear on two points: She was directly involved in the CIA’s black-site torture of war-on-terror detainees, as well as the subsequent destruction of videotaped evidence of that abuse.

The journey to redemption is long and often tempest-tossed. But the American Psychological Association (APA) took another noteworthy step last week when CEO Arthur Evans Jr. sent a letter to the Senate Intelligence Committee, expressing concern over President Trump’s nomination of Gina Haspel as director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Amid heated debate over whether Haspel is qualified or appropriate for the position, the public record is clear on two points: She was directly involved in the CIA’s black-site torture of war-on-terror detainees, as well as the subsequent destruction of videotaped evidence of that abuse.

APA’s opposition to Haspel is consistent with its stated mission of advancing psychology to benefit society, improve people’s lives, and promote human rights. Dozens of other organizations with similar commitments—including the Center for Victims of Torture, the Coalition for an Ethical Psychology, Physicians for Human Rights, Psychologists for Social Responsibility, and Torture Abolition and Survivors Support International—have also weighed in strongly against the Haspel nomination.

For health professionals, this stance reflects a shared understanding: Torture is a barbaric assault on human dignity, and it is therefore intrinsically and profoundly psychological. For survivors, the demons of deep psychic wounds continue without end. Overwhelming feelings of helplessness, brokenness, and disconnection from other people are the direct result of having been subjected to agonizing abuse and humiliation at the hands of another human being. Haunting flashbacks and nightmares are abiding reminders that safety and solace are exceedingly difficult if not impossible to attain.

But the APA’s rejection of Haspel as CIA director speaks even louder given the association’s past failure to stand as a bulwark against the kind of abusive detainee treatment she oversaw. In the immediate aftermath of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Vice President Dick Cheney told the nation that the Bush Administration would work “the dark side,” spend time “in the shadows,” use “any means at our disposal,” and make certain that “we have not tied the hands of our intelligence communities.” APA’s leaders responded by reaching out directly to the Department of Defense (DoD) and the CIA, explicitly “offering psychologists’ expertise to decision-makers” in these and other related agencies.

That began a years-long, ill-conceived odyssey for the APA. Those at the helm repeatedly steered the organization into perilous and turbulent waters, eschewing the safe harbor and terra firma of the profession’s bedrock do-no-harm ethics. They did so to ensure that psychologists would always be essential participants in the government’s burgeoning detention and interrogation operations. Despite facile, reassuring claims that these operations were “safe, legal, ethical, and effective,” they were brutal and ruthless. One APA member, James Mitchell, designed and implemented the CIA’s gruesome torture techniques. Other APA members were stationed at Guantanamo Bay, where DoD torture and abuse took place.

The APA’s misguided choices, over more than a decade, have been chronicled in numerous statements, articles, and detailed reviews—and most extensively in the 2015 Hoffman Report. Following that report, the association’s governing council overwhelmingly approved a resolution that banned psychologists from involvement in national security interrogations and affirmed that psychologists present at Guantanamo and similar international sites are in violation of APA policy unless they are working directly on behalf of the detainees or providing treatment to military personnel.

This redemptive course correction has been buffeted by headwinds from a faction of psychologists—including some members of the military intelligence establishment—who have aligned themselves with those implicated in the institutional betrayal that characterized APA’s troubled past. Their efforts aimed at turning back the clock have included lawsuits, ethics complaints, and proposals to reverse the recent reforms and remove the Hoffman Report from the APA’s website. Even more extreme, some of these critics argue that the APA has become “a willing co-conspirator to the likes of al Qaeda and ISIS.”

In key ways, then, the APA’s opposition to Gina Haspel’s nomination is important symbolically even if its immediate practical impact proves limited. It comes at a fraught time when forces both within and beyond the association are moving to advance regressive policy prescriptions that are likely to endanger the cause of human rights and respect for human dignity. That is more than reason enough to applaud this action, while at the same time remaining vigilant about darkening clouds that may yet again threaten APA in the months ahead.